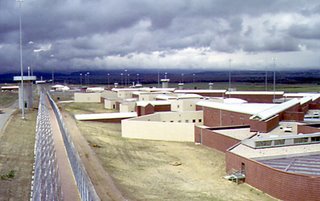

Life in the Supermax Prison

Because it's so different from any other residential facility and goes so far beyond any other extreme life-style, life in a supermax prison holds an undeniable fascination. This is compounded by the relative secrecy that surrounds the supermax prison walls and the psychological and philosophical questions that arise from supermax confinement.

Apart from punishment and retribution, one of the many justifications of supermax incarceration of terrorists and heinous criminals is to keep them quiet and deprive them of contact with those who might condone, celebrate, or glorify their anti-social activities. But despite societal efforts to remove and restrict communication with supermaxed prisoners, word has been getting out. And what is revealed is that life, at least for some, in a supermax prison may be pretty much the same as in any other high security institution, regardless of how extreme the living conditions.

What prompts this observation is disclosure of a letter written by actor Woody Harrelson's father, convicted professional gambler and murderer Charles Harrelson, from his supermax prison cell in Florence, Colorado. Harrelson died a few weeks ago at the age of 69 after suffering a heart attack. Harrelson, it might be remembered, was convicted of murdering U.S. District Judge John H. Wood in 1979 in a murder-for-hire scheme. As reported in the San Antonio Express-News a few days ago, Harrelson was allegedly paid $250,000 to murder Judge Wood, who was then presiding over the San Antonio, Texas, drug trial of accused drug dealer Jimmy Chagra.

What prompts this observation is disclosure of a letter written by actor Woody Harrelson's father, convicted professional gambler and murderer Charles Harrelson, from his supermax prison cell in Florence, Colorado. Harrelson died a few weeks ago at the age of 69 after suffering a heart attack. Harrelson, it might be remembered, was convicted of murdering U.S. District Judge John H. Wood in 1979 in a murder-for-hire scheme. As reported in the San Antonio Express-News a few days ago, Harrelson was allegedly paid $250,000 to murder Judge Wood, who was then presiding over the San Antonio, Texas, drug trial of accused drug dealer Jimmy Chagra.Anyway, as now reported in a Denver Post article, Charles Harrelson was not only acclimated to life in the supermax prison, but he even found much to like about it. The article cites a "chatty, six-page letter" Harrelson wrote to a friend, a Denver attorney.

In the letter, Harrelson "wrote eloquently about a peaceful, silent existence of reading and writing" and about watching television and listening to the radio. He reportedly enjoyed David Letterman, National Public Radio, and the BBC. He filled his days with "reading, writing, or doing chores;" he frequently wrote to his wife and family. Observing that he was never bored, Harrelson said, "There are not enough hours in a day for my needs."

According to Harrelson, "The silence is wonderful. And feeling left alone is great . . . . nobody bothers me." Savoring his ability to "take a shower anytime, stay awake all night if I wish," Harrelson described his solitary life as "something akin to independence."

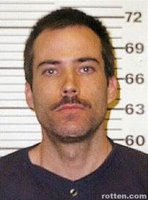

A few months ago, Time Magazine gave a vastly different view of the same supermax prison: Inside Bomber Row, by Maryanne Vollers. Writing to his mother and to Vollers, the author of a book about him, convicted bomber Eric Rudolph reported that the prison resounded:

with the constant mechanical whir and clank of electronic gates, punctuated by the sound of inmates praying, wailing and shouting conversations in English and Arabic through the walls and vents between their cells.One of the most fascinating parts of Rudolph's report from inside the supermax prison concerned some of the ways the prisoners are "entertained." According to Rudolph, prisoners are offered "crossword puzzles, bingo and Jeopardy competitions through flyers or through a closed-circuit TV channel. . . . The winners are rewarded with a candy bar or a picture of themselves." Rudolph, like Harrelson, enjoys the prison's closed-circuit cable TV, saying "he gets 60 channels, including music radio stations and local news."

Writing in 2005, a few months after he arrived, Rudolph said "It is Ramadan now and the Muslims are fasting. The call to prayer echoes through the halls five times a day giving this place a decidedly otherworldly feel."

Unlike Harrelson, who appeared content with his living conditions, Rudolph complained in his letters about increasingly severe conditions, including cold food, delayed mail, and missed exercise caused by a shortage of staff. According to Rudolph, after the increasingly less frequent times out of their cells for exercise, the guards slowly move the prisoners back, "And then we sit in our darkened cells for the rest of the week, staring out at the empty sun-drenched yard."

Through the slit window one can see the sky, but other than this and the few small birds that roost on the prison roof, there are no signs of the natural world